The purpose of click-through rates is to measure the ratio of clicks to impressions of an online ad or email marketing campaign. Generally the higher the CTR the more effective the marketing campaign has been at bringing people to a website. Most commercial websites are designed to elicit some sort of action, whether it be to buy a book, read a news article, watch a music video, or search for a flight. People rarely visit websites with the intention of viewing advertisements, in the same way that few people watch television to view the commercials.

Here we are going to look at whether organic CTR as compared to paid CTR has an impact on your SEO rankings, and if so, how.

Impact of Organic CTR on SEO Rankings

Below is a compilation of data that explains in detail the above mentioned point, by Moz.

Google (OK, at least one Google engineer who spoke at SMX) seems to indicate the latter is indeed the case:

I also highly encourage you to check out Rand Fishkin’s Whiteboard Friday discussing clicks and click-through rate. In short, the key point is this: If a page is ranking in position 3, but gets a higher than expected CTR, Google may decide to rank that page higher because tons of people are obviously interested in that result.

Seems kind of obvious, right?

And if true, we ought to be able to measure it! In this post, I’m going to try to show that RankBrain may just be the missing link between CTR and rankings.

Untangling meaning from Google RankBrain confusion

Let’s be honest: Suddenly, everyone is claiming to be a RankBrain expert. RankBrain-shaming is quickly becoming an industry epidemic.

Please ask yourself: Do most of these people — especially those who aren’t employed by Google, but even some of the most helpful and well-intentioned spokespeople who actually work for Google — thoroughly know what they’re talking about? I’ve seen a lot of confusing and conflicting statements floating around.

Here’s the wildest one. At SMX West, Google’s Paul Haahr said Google doesn’t really understand what RankBrain is doing.

If this really smart guy who works at Google doesn’t know what RankBrain does, how in the heck does some random self-proclaimed SEO guru definitively know all the secrets of RankBrain? They must be one of those SEOs who “knew” RankBrain was coming, even before Google announced it publicly on October 26, but just didn’t want to spoil the surprise.

Now let’s go to two of the most public Google figures: Gary Illyes and John Mueller.

Illyes seemed to shoot down the idea that RankBrain could become the most important ranking factor (something which I strongly believe is inevitable). Google’s Greg Corrado publicly stated that RankBrain is “the third-most important signal contributing to the result of a search query.”

Illyes also said on Twitter that: “Rankbrain lets us understand queries better. No affect on crawling nor indexing or replace anything in ranking.” But then later clarified: “…it does change ranking.”

I don’t disagree at all. It hasn’t. (Not yet, anyway.)

Links still matter. Content still matters. Hundreds of other signals still matter.

It’s just that RankBrain had to displace something as a ranking signal. Whatever used to be Google’s third most important signal is no longer the third most important signal. RankBrain couldn’t be the third most important signal before it existed!

Now let’s go to Mueller. He believes machine learning will gain more prominence in search results, noting Bing and Yandex do a lot of this already. He noted that machine learning needs to be tested over time, but there are a lot of interesting cases where Google’s algorithm needs a system to react to searches it hasn’t seen before.

Bottom line: RankBrain, like other new Google changes, is starting out as a relatively small part of the Google equation today. RankBrain won’t replace other signals any time soon (think of it simply like this: Google is adding a new ingredient to your favorite dish to make it even tastier). But if RankBrain delivers great metrics and keeps users happy, then surely it will be given more weight and expanded in the future.

RankBrain headaches

If you want to nerd out on RankBrain, neural networks, semantic theory, word vectors, and patents, then you should read:

- Getting Your Head Around Google’s RankBrain by David Harry

- RankBrain: What Do We Know About Google’s Machine-Learning System? by Virginia Nussey (concentrate on Marcus Tober’s SMX presentation recap in the section “Machine Learning Ranks Relevance”)

- How Google Works: A Google Ranking Engineer’s Story by Kristi Kellogg

To be clear: my goal with this post isn’t to discuss tweets from Googlers, patents, research, or speculative theories.

Rather, I’m just going to ignore EVERYBODY and look at actual click data.

Searching for Rankbrain

Rand conducted one of the most popular tests of the influence of CTR on Google’s search results. He asked people to do a specific search and click on the link to his blog (which was in 7th position). This impacted the rankings for a short period of time, moving the post up to 1st position.

But these are all transient changes. Changes don’t persist.

It’s like how you can’t increase your AdWords Quality Scores simply by clicking on your own ads a few times. This is the oldest trick in the book and it doesn’t work.

The results of another experiment appeared on Search Engine Land last August and concluded that CTR isn’t a ranking factor. But this test had a pretty significant flaw — it relied on bots artificially inflating CTRs and search volume (and this test was only for a single two-word keyword: “negative SEO”). So essentially, this test was the organic search equivalent of click fraud. Google AdWords has been fighting click fraud for 15 years and they can easily apply these learnings to organic search. What did I just say about old tricks?

Before we look at the data, a final “disclaimer.” I don’t know if what this data reveals is definitively RankBrain, or another CTR-based ranking signal that’s part of the core Google algorithm. Regardless, there’s something here — and I can most certainly say with confidence that CTR is impacting rank. For simplicity, I’ll be referring to this as Rankbrain.

A crazy new experiment

Google has said that RankBrain is being tested on long-tail terms, which makes sense. Google wants to start testing its machine-learning system with searches they have little to no data on — and 99.9 percent of pages have zero external links pointing to them.

So how is Google able to tell which pages should rank in these cases? By examining engagement and relevance. CTR is one of the best indicators of both.

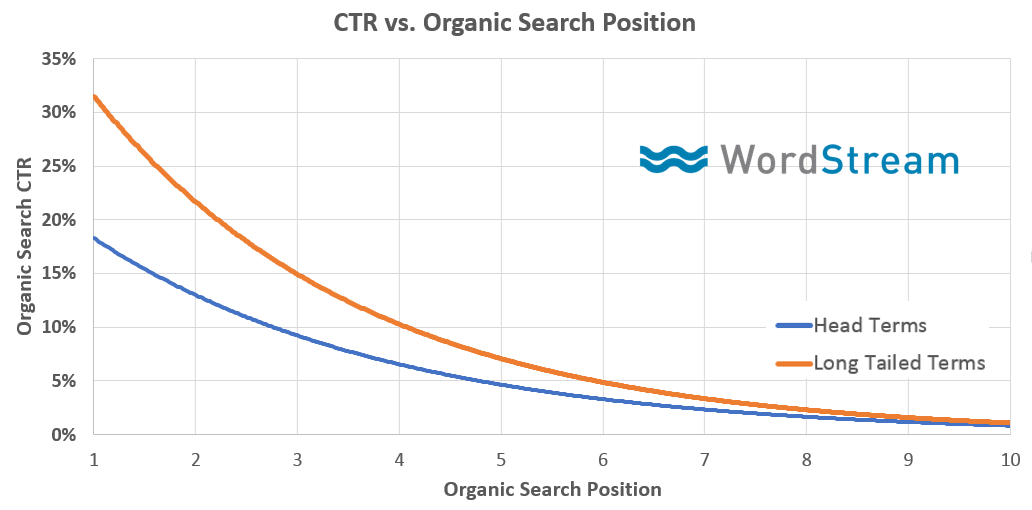

Head terms, as far as we know, aren’t being exposed to RankBrain right now. So by observing the differences between the organic search CTRs of long-tail terms versus head terms, we should be able to spot the difference:

We used 1,000 keywords in the same keyword niche (to isolate external factors like Google shopping and other SERP features that can alter CTR characteristics). The keywords are all from my own website: Wordstream.com.

I compared CTR versus rank for 1–2 word search terms, and did the same thing for long-tail keywords (4–10 word search terms).

Notice how the long-tail terms get much higher average CTRs for a given position. For example, in this data set, the head term in position 1 got an average CTR of 17.5 percent, whereas the long-tail term in position 1 had a remarkably high CTR, at an average of 33 percent.

You’re probably thinking: “Well, that makes sense. You’d expect long-tail terms to have stronger query intent, thus higher CTRs.” That’s true, actually.

But why is that long-tail keyword terms with high CTRs are so much more likely to be in top positions versus bottom-of-page organic positions? That’s a little weird, right?

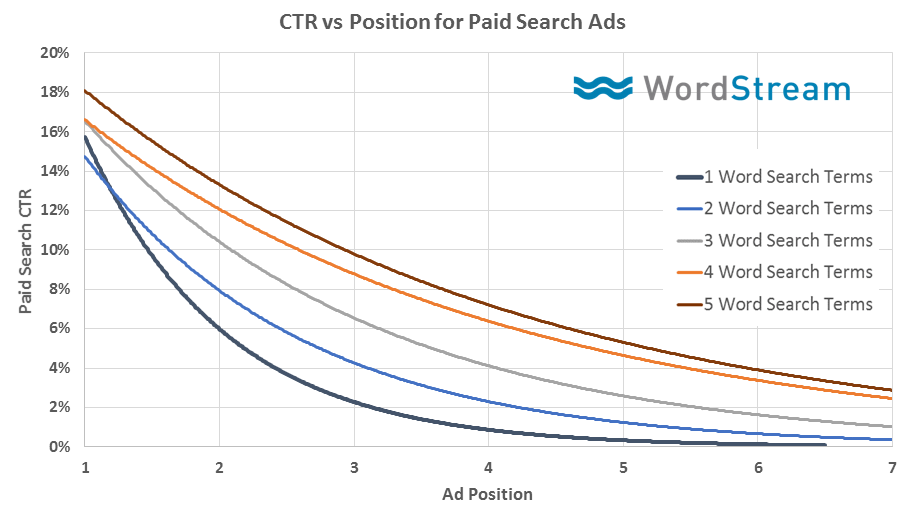

OK, let’s do an analysis of paid search queries in the same niche. I use organic search to come up with paid search keyword ideas and vice versa, so we’re looking at the same keywords in many cases.

Long-tail terms in this same vertical get higher CTRs than head terms. However, the difference between long-tail and head term CTR is very small in positions 1–2, and becomes huge as you go out to lower positions.

So in summary, something unusual is happening:

- In paid search, long-tail and head terms do roughly the same CTR in high ad spots (1–2) and see huge differences in CTR for lower spots (3–7).

- But in organic search, the long-tail and head terms in spots (1–2) have huge differences in CTR and very little difference as you go down the page.

Why are the same keywords behaving so differently in organic versus paid?

The difference (we think) is that RankBrain is boosting the search rankings of pages that have higher organic click-through rates.

Not convinced yet?